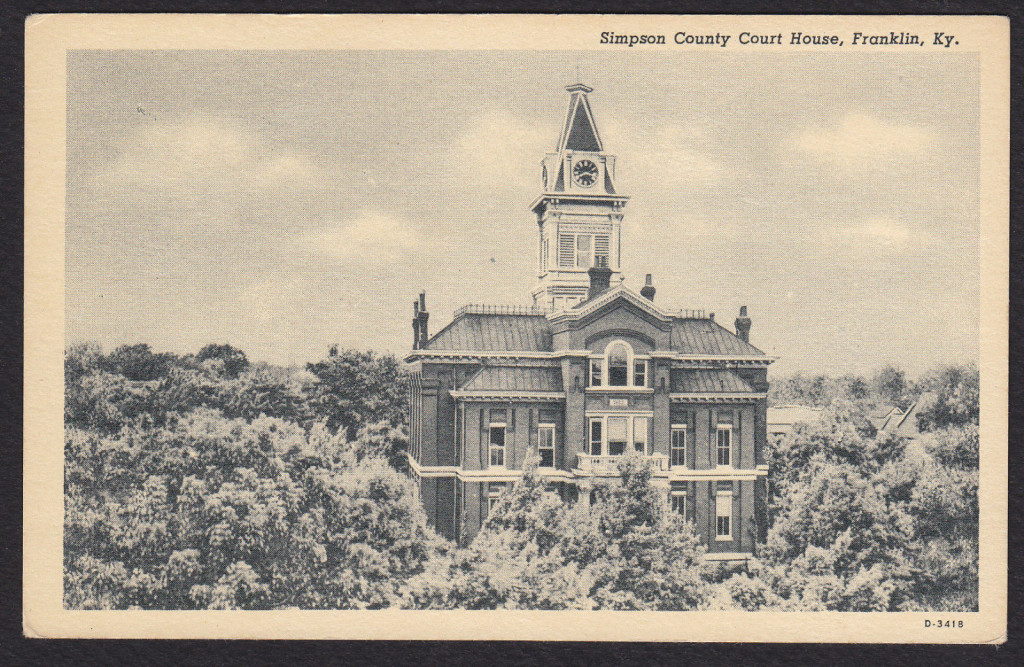

Simpson County Courthouse, Franklin, Kentucky. Built in 1882. Listed in National Register of Historic Places in 1980. For a more detailed history, see below.

Published Court of Appeals appellate cases for this week – January 22, 2015: Links are to full text of PDF decision with AOC.

83. Premises Liability. Expert Witnesses. Independent Contractor vs. Employee.

Auslander Properties, LLC vs. Joseph Herman Nalley

Court of Appeals Published Opinion Affirming – Nelson County

STUMBO, JUDGE: Auslander Properties, LLC, appeals from a Judgment of the Nelson Circuit Court reflecting a jury verdict in favor of Plaintiffs-Appellees Joseph Herman Nalley, et al., in their premises liability and loss of consortium action. Auslander Properties, LLC, contends that the trial court erred in applying OSHA/KOSHA to the facts of this case, by allowing an expert witness to improperly testify as to matters of law reserved for the court, and by allowing treating physicians and a nurse to offer improper testimony at trial. For the reasons stated below, we find no error and AFFIRM the Judgment on appeal.

KRS 446.070 provides that, “[a] person injured by the violation of

any statute may recover from the offender such damages as he sustained by reason of the violation, although a penalty or forfeiture is imposed for such violation.” Such a statute “creates a private right of action in a person damaged by another person’s violation of any statute that is penal in nature and provides no civil remedy, if the person damaged is within the class of persons the statute intended to be protected.” Hargis, 168 S.W.3d at 40 (citing State Farm Mut. Auto. Ins. Co. v. Reeder, 763 S.W.2d 116, 118 (Ky. 1988)); see also Grzyb v. Evans, 700 S.W.2d 399, 401 (Ky. 1985); Hackney v. Fordson Coal Co., 230 Ky. 362, 19 S.W.2d 989, 990 (1929). The Hargis court went on to hold that KRS 338.031(1)(b), the statute under which the KOSHA regulations were promulgated, specifically provides that “[e]ach employer . . . [s]hall comply with occupational safety and health standards promulgated under this chapter.” Since those standards are promulgated in the regulations adopted by the Kentucky Occupational Safety and Health Standards Board, KRS 338.051(3) and KRS 338.061(1), the violation of a KOSHA regulation would constitute a violation of KRS 338.031(1)(b), thus triggering the right of action created by KRS 446.070. Hargis, 168 S.W.3d at 41-42.

The clear language of Hargis refutes the LLC’s argument on this issue. Prior to the Hargis decision, Teal v. E.I. DuPont de Nemours and Co., 728 F.2d 799 (6th Cir. 1984), stood for the proposition that OSHA (and by implication KOSHA) applied not only to direct employees, but also to employees of independent contractors.

We review the trial court’s rulings on the admission of expert testimony under an abuse of discretion standard. Goodyear Tire and Rubber Co. v. Thompson, 11 S.W.3d 575, 577-78 (Ky. 2000). Abuse of discretion is found where the trial court’s decision is “arbitrary, unreasonable, unfair, or unsupported by sound legal principles.” Commonwealth v. English, 993 S.W.2d 941, 945 (Ky. 1999). In the matter at bar, Gray testified as to matters outside the common knowledge of the jurors, and assisted rather than impeded them in the solution of the ultimate problem. Werner, supra. We cannot conclude that the admission of Gray’s testimony was arbitrary, unreasonable, unfair, or unsupported by sound legal principles. As such, we find no error on this issue.

Lastly, the LLC contends that the trial court erred in allowing Nalley’s treating physicians and a registered nurse to offer improper testimony. It argues that the treating physicians testified beyond the opinions disclosed within their reports despite not being identified as expert witnesses under Kentucky Rule of Civil Procedure (CR) 26.02, and that the nurse improperly testified as to Nalley’s future medical needs when only a medical doctor is qualified to make such determinations. We have closely examined the record and the law on this issue, and find no error. Treating physicians may testify as “to the facts they had learned and the opinions they had formed based on first-hand knowledge and observation.” Charash v. Johnson, 43 S.W.3d 274, 280 (Ky. App. 2000). This is true though the physicians are not certified as experts. Id. The decision to allow such testimony is left to the sound discretion of the trial court. Goodyear Tire and Rubber Co., supra. The nurse at issue, Linda Dierking, testified as an expert life care planner at trial. We find no basis in the law for concluding that her opinion regarding Nalley’s future life care needs improperly supplanted the opinions of medical doctors, nor otherwise ran afoul of the law or the civil rules. We cannot conclude that the trial court abused its discretion in allowing her testimony, and find no error on this issue.

91. Attorney Fees

Gregory Dwayne Hunt vs North American Stainless

COA Not to Be Published Opinion Affirming – Carroll County

THOMPSON, JUDGE: This matter is before the Court for the second time on an appeal of an award of attorney fees. In Hunt v. North America Stainless, No. 2012- CA-000098-MR, 2014 WL 1881891 (Ky.App. 2014) (unpublished), we reversed and remanded for additional findings of fact and a new award of attorney fees. Gregory Dwayne Hunt and his attorneys as real parties in interest (Garry R. Adams, Daniel J. Canon, Mellissa Eyre Yeagle and A. Pete Lay) argue the circuit court abused its discretion on remand by awarding $3,000 in attorney fees rather than the $37,460.05 requested. Having reviewed the record, the arguments of the parties and applicable law, we affirm.

KRS 337.385(1), specifically provides a prevailing employee may receive “such reasonable attorney’s fees as may be allowed by the court.” In interpreting a similar provision under the Kentucky Consumer Protection Act, KRS 367.220(3), the Kentucky Supreme Court determined the phrase “the court may award . . . reasonable attorney’s fees” authorized, but did not mandate, an award of attorney fees and the decision of whether to award attorney fees was subject to the sound discretion of the trial court. Alexander v. S & M Motors, Inc., 28 S.W.3d 303, 305 (Ky. 2000). However, in making such a determination, the trial court should consider whether awarding fees would keep “the courthouse door open for those aggrieved by violations of the act.” Id. at 306.

Simply because a party succeeds under one claim under KRS Chapter 337 does not mean all of the party’s attorney fees within the same litigation can be recovered. KRS 337.385 does not allow for an expanded award of fees for ancillary actions or defenses, even if the party prevails. See Hensley, 461 U.S. at 434-35, 103 S.Ct. at 1940 (discussing the exclusion of fees expended on unsuccessful, unrelated claims). Therefore, it is the burden of the prevailing party to clearly establish entitlement to an award under KRS Chapter 337 by properly documenting appropriate hours expended and hourly rates for this claim. See Hensley, 461 U.S. at 437, 103 S.Ct. at 1941. Where the documentation is inadequate, the court may reduce the award accordingly. Id. at 433, 103 S.Ct. at 1939.

The circuit court was correct in focusing on calculating reasonable fees based on Hunt’s wage-and-hour counterclaim and not on the time for defending the NAS breach of contract claim. The circuit court properly used the lodestar approach to calculate reasonable attorney fees by evaluating whether the requested rate was reasonable in relation to the claim, the claim’s novelty and difficulty, and the number of the hours to be attributed strictly to that claim when it had essentially been resolved prior to trial. The circuit court acted properly in developing a blended rate where it could not attribute where the hours of each attorney was spent in relationship to the different parts of the case. Additionally, the amount awarded was sufficient to allow access to court for enforcement of timely payment of Hunt’s wages.

Historical note on Franklin County Courthouse.

Simpson County Kentucky was created by a Legislative Act of 28 January 1819 from Logan, Warren, and Allen Counties. Simpson County was named in honor of Captain John Simpson, an early Indian fighter who fought at Fallen Timber and was one of many Kentucky victims at River Raisin. Simpson County’s Third Courthouse built in 1882 after the second courthouse burned down. Located in Franklin, Ky. Designed by Louisville architects, McDonald Brothers. Wings were added in 1962 in an attempt to match the original style. This courthouse was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1980. The McDonald Architect firm also designed the First Franklin Presbyterian Church (1886); the Franklin Female College (1889); and the Goodnight House (1893). The first courthouse was a log building. The second courthouse was a two story brick building with a cupola. A fire pump and hoses were suggested but not installed, and in May 1862 this second courthouse burned down. For what it is worth, arson had been attempted two times previously before succeeding on this third attempt. Most of the county records (deeds, wills, and marriages) were destroyed when the court house burned on May 17, 1882. However many of the Circuit Court records survived and were stored for many years in the attic of the present courthouse. These order books have been microfilmed and are on file at the Kentucky State Archives in Frankfort, KY. The loose records have been indexed and along with the original order books are on file at the Simpson County Archives in Franklin, KY. In fact, all records which are available for genealogical/historical research can be found at the Simpson County Archives at 206 North College St, Franklin, KY.

There are some good injury and insurance law reads below.

Selected “not to be published” Opinions–

79. Premises Liability. Open and Obvious Doctrine. Reversed summary judgment dismissal.

Bonita Cobb vs. Joseph Kamer

COA Not to Be Published Opinion Vacating and Remanding – Fayette

TAYLOR, JUDGE: This matter is before the Court of Appeals on remand from the Kentucky Supreme Court by Opinion and Order entered October 21, 2015, in Appeal No. 2014-SC-000191-D. The Supreme Court vacated and remanded the Court of Appeals Opinion affirming, for further consideration in light of the recent Supreme Court decision rendered in Carter v. Bullitt Host, LLC, 471 S.W.3d 288 (Ky. 2015).

This case looks to the application of the open and obvious doctrine to negligence cases involving obvious natural outdoor hazards. Prior to Carter v. Bullitt Host, 471 S.W.3d 288, the general rule in Kentucky was that natural outdoor hazards which were as obvious to an invitee as to the owner of a premises, did not constitute an unreasonable risk which the owner owed a duty to warn or remove. Standard Oil v. Manis, 433 S.W.2d 856 (Ky. 1968). This rule was buttressed by the Supreme Court in Corbin Motor Lodge v. Combs, 740 S.W.2d 944 (Ky. 1987), holding that a defendant owed no duty to a plaintiff to warn of outdoor natural hazards. This effectively established a special category for outdoor natural hazards in the legal analysis of the open and obvious doctrine. This limited exception survived the adoption of comparative fault in Kentucky tort law in Hilen v. Hays, 673 S.W.2d 713 (Ky. 1984), and Kentucky River Medical Center v. McIntosh, 319 S.W.3d 385 (Ky. 2010) and its progeny. Kentucky River effectively held that the open and obvious rule was a vestige of contributory negligence and was no longer the law in Kentucky, subject to a few exceptions, including outdoor natural hazards, as set forth in Manis, 433 S.W.2d 856.

However, in Carter v. Bullitt Host, LLC, 471 S.W.3d 288, the Kentucky Supreme Court has expressly overruled Standard Oil v. Manis, 433 S.W.2d 856, which now mandates judicial review of outdoor natural hazards under 1 The Court of Appeals decision affirming was rendered on March 14, 2014, before Carter v. Bullitt Host, LLC, 471 S.W.3d 288 (Ky. 2015) was rendered on September 24, 2015. -2- comparative fault principles. Having stated the premise for our reconsideration of this case based upon the Supreme Court mandate, we will again restate the relevant facts in this case.

While the Supreme Court has not closed the door to granting summary judgments in open and obvious danger cases involving outdoor natural hazards, it will be substantially limited going forward under the comparative fault analysis referenced above. Given the Supreme Court’s mandate, we have no alternative based on the record before this Court on appeal but to vacate the summary judgment entered below in this case and remand for further proceedings consistent with Carter v. Bullitt Host, LLC, 471 S.W.3d 288 (Ky. 2015).

For the foregoing reasons, the summary judgment of the Fayette Circuit Court is vacated and remanded for further proceedings consistent with this opinion.

84. Attorney Fees in PIP Suit.

Marquita Hamlet vs. Allstate Insurance Co.

COA Not to Be Published Opinion Affirming – Jefferson County

NICKELL, JUDGE: Marquita Hamlet has appealed from the January 29, 2014, order of the Jefferson Circuit Court denying her motion for interest and attorney’s fees she claimed were due from Allstate Insurance Company based on its alleged improper denial of payment of basic reparations benefits (BRB) due her. Following a careful review, we affirm.

NICKELL, JUDGE: Marquita Hamlet has appealed from the January 29, 2014, order of the Jefferson Circuit Court denying her motion for interest and attorney’s fees she claimed were due from Allstate Insurance Company based on its alleged improper denial of payment of basic reparations benefits (BRB) due her. Following a careful review, we affirm.

Hamlet presents this Court with compelling legal and policy arguments supportive of her position that payment of interest and attorney’s fees are proper remedies for the unreasonable denial of BRB payments. In fact, there appears to be no dispute as to the correctness of her legal position. We are convinced her basic statements of law are indeed correct and warrant no further discussion. Nevertheless, however correct the law she cites, Hamlet’s claims must fail based upon the facts underlying this matter.

Hamlet’s contention that Allstate acted unreasonably is premised upon four flawed assumptions: 1) she was legally entitled to no-fault benefits; 2) her eligibility was confirmed by the KACP prior to assignment of her claim to Allstate; 3) no good faith basis for denying her eligibility existed; and, 4) she completely cooperated with Allstate and complied with the statutory mandates. Unfortunately for Hamlet, the record does not bear out her assumptions.

Under the express terms of KRS 304.39-210(1), benefits

become “overdue if not paid within thirty (30) days after the reparation obligor receives reasonable proof of the fact and amount of loss realized . . . .” Hamlet cites this statute in support of her allegation that any delay in payment beyond thirty days is per se unreasonable. However, we believe Hamlet’s argument misses the mark and overlooks a simple but key phrase. The plain language of the statute indicates the thirty-day period does not begin running on the date an application is referred to a KACP member for servicing, but rather is tolled until “reasonable proof” of the loss is received by the servicing insurer. We decline Hamlet’s invitation to define a bright-line rule that any delay in excess of thirty days is per se unreasonable. To do so would likely invite unscrupulous litigants to manipulate the system to create delays in pursuit of financial gain. We cannot countenance such a result.

What is clear from the record on appeal is that Allstate’s requests for information were not unreasonable, unduly burdensome, or outside the bounds of the KACP or MVRA. Rather, they appear to have been tailored to gather only the information necessary upon which to properly base an eligibility determination. Once all of this information was finally produced, Allstate promptly completed its eligibility determination and tendered the appropriate amount of benefits due. Hamlet cannot say she has clean hands when the record reveals the lack of cooperation in the investigation phase which created the delay of which she now complains. The delay was reasonable under the circumstances as the trial court correctly concluded. Thus, Hamlet was not entitled to the statutory remedies of 18% interest on any overdue payments or attorney’s fees, as soundly found by the trial court. There was no error.

86. Legal Malpractice, Statute of Limitations, Title Search and Duties Owed

Kevin Kurtsinger vs. William L. Patrick

COA Not to Be Published Opinion Affirming summary judgment dismissing legal malpractice claim (Anderson Cir Ct)

88. Judicial admissions in criminal trial used as collateral estoppel in civil auto accident injury trial

Melva Moffett vs. Manning P. Shaw

COA Not to Be Published Opinion affirming summary judgment dismissing injury claim (McCracken)

The appellants maintain that the trial court erred in granting the summary judgment because an issue of material fact still exists as to who was the driver of the Yanezes’ vehicle. Shaw, however, counters that the summary judgment was appropriate because Yanez pled guilty and was sentenced to ten years’ imprisonment. Consequently, based on Yanez’s judicial admission, Shaw argues that under the doctrine of collateral estoppel, there is no issue of material fact. After a careful review of the record, the briefs, and the law, we affirm.

90. Underinsured motorist benefits, Coots Notice

Sharon Spalding vs. Auto-Owners Ins. Co.

COA Not to Be Published Opinion Reversing and remanding summary judgment dismissing claim for underinsured motorist benefits when Coots notice not given to UIM Carrier but who had told plaintiff initially no UIM coverages

Basically, Sharon Spalding injured in car collision, KFBM tendered its $25k liability limits, Sharon’s counsel contacted Sharon’s insurer and learned from local agent (Sharon Spalding, no relative with Energy Insurance) that there were NO UIM coverages. Sharon settled with KFBM liability, but then counsel learned there was actually $100,000 in UIM coverages through Energy with Auto-Owners. Sharon made a claim for UIM and trial court granted summary judgement in favor of Auto Owners since no compliance with Coots notice (KRS 304.39-320) and made claim. Auto-Owners was sued for the UIM benefits.

COA reversed and remanded case consistent with this opinion, stating:

Appellant’s argument centers on her contention that the Appellee is bound by the acts of its sales agent, and Appellee therefore cannot rely on the lack of a Coots notice as a basis for denying UIM coverage. Appellant directs our attention to statutory law providing that an individual who sells insurance is an agent of the carrier, KRS 304.9-020(1), and argues that it would be inequitable to allow Appellee to escape coverage under these circumstances. She goes on to argue that Appellee was not prejudiced by the settlement, and that the circuit court’s apparent reliance on Kentucky Farm Bureau Mutual Insurance Company v. Young, 317 S.W.3d 43 (Ky. 2010), is misplaced. * * *

When viewing the record in a light most favorable to Appellant and resolving all doubts in her favor, we must conclude that Summary Judgment was improperly rendered. The matter before us focuses on inquires made by Attorney George and/or his paralegal Gloria George to Brenda Spalding and/or Energy Insurance regarding whether Appellant had UIM coverage. Appellee asserts that this inquiry represents a question of law rather than a question of fact, and in so doing contends that Brenda Spalding had no duty to correctly answer a question of law. In examining the limited record, however, we cannot discern if the Marion Circuit Court addressed this issue. That is to say, it has not been established whether Brenda Spalding’s response to George’s inquiry constituted an act of non- feasance which can be imputed to Appellee. An additional question of law exists as to whether this purported act of non-feasance, if imputed to Appellee, operates as a waiver to the Coots notice requirement. A mixed question of law and fact also remains as to whether Brenda Spalding, as owner of Energy Insurance, was an agent of Appellee. And finally, an additional question remains as to whether Appellant’s failure to notify George that she owned the Ford Focus affects this calculus. According to George’s deposition, Appellant never informed him that she owned a Ford Focus, and he learned of it only after securing the settlement with Kentucky Farm Bureau on the liability claim against Robinson.

Because this matter reached us via Summary Judgment, we are bound to construe these issues in favor of the non-movant, Appellant, and to resolve all doubts in her favor. Steelvest, supra. That is to say, we must examine whether the Marion Circuit Court correctly concluded that there were no genuine issues of material fact, and that Appellee was entitled to a Judgment as a matter of law. Scifres, supra. Given the foregoing, and resolving all doubts in favor of Appellant, we cannot conclude that Appellee was so entitled.

Accordingly, we REVERSE the Summary Judgment of the Marion Circuit Court and REMAND the matter for further proceedings consistent with this Opinion.

Click here for links to all the archived AOC Court of Appeals minutes at the web site for the Administrative Office of the Courts.

Click here for a listing of the Kentucky Court Report’s posts of the weekly COA minutes (or you can always access these within the KCR web site at the uppermost dropdown menu option for the Court of Appeals).

AOC version of this week’s decisions can be accessed by clicking here.

The complete set of this week’s minutes listing all decisions (published and not to be published) with links to the full text of each at the AOC, are below:

[gview file=”https://kycourtreport.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/MNT01292016-1.pdf”]